Climate, Crops, and Pests

Cross Impacts on Potato and Faba Bean (2023–2025 Growing Seasons)

Nicolas Palacios Bett

The relationship between climate and crops is one of the pillars of food security in the high Andean regions. From the experimental farm of Moray, located at 3,550 m a.s.l., we observed during the 2023–2024 season (September 2023 to August 2024) and the 2024–2025 season (September 2024 to August 2025) how climatic variability can completely transform the behavior of two key crops in the Andean diet: potato (Solanum tuberosum) and faba bean (Vicia faba). Although both are adapted to extreme conditions, they respond very differently depending on the environmental context. Understanding these nuances not only enriches research but also provides practical tools for farmers, technicians, and students working in high-altitude farming systems, where climate and crops are central to food security.

In the comparative analysis of these two seasons, we documented how climate interacts with crop development. In potato, the main phytosanitary problem was late blight, a disease that causes rot in leaves and tubers. In contrast, faba bean was mainly affected by leafminer flies, which tunnel through leaves and cause wilting. Interestingly, these pests thrive under opposite climatic conditions: late blight prospers under high humidity and intense rainfall, while leafminers increase during dry and warm periods. Below, we describe how these conditions manifested in each growing season.

To analyze phytosanitary problems, we applied the concept of the “disease triangle,” which emphasizes that every disease arises from the interaction of three inseparable elements: the causal agent (pest or pathogen), the host (the plant), and the environment (temperature, humidity, and rainfall). While climate itself cannot be modified, this framework shows that applied knowledge allows farmers to adapt agricultural practices, reducing risks through timely management decisions. Strategies such as staggered planting, protective covers, crop rotation, and diversification help buffer the effects of adverse years. Crop associations in Moray strengthen soil biodiversity and activate natural mechanisms that reduce pest incidence, integrating traditional knowledge with agroecological principles.

This report integrates complementary perspectives from climate science, agronomy, and biotechnology through the collaborative work of Pierina Milla (physical and climate sciences), John Checca (agronomy and field management), and Nicolas Palacios (biology and agricultural biotechnology). These interdisciplinary viewpoints made it possible to evaluate the impact of climatic conditions on crop health while also considering local agricultural practices from a contextualized scientific approach. The goal was to generate useful information for planning future growing seasons and strengthening adaptive management strategies in Andean regions exposed to increasing climatic variability, including frosts, heavy rains, and droughts.

1. Papa (Solanum tuberosum L.)

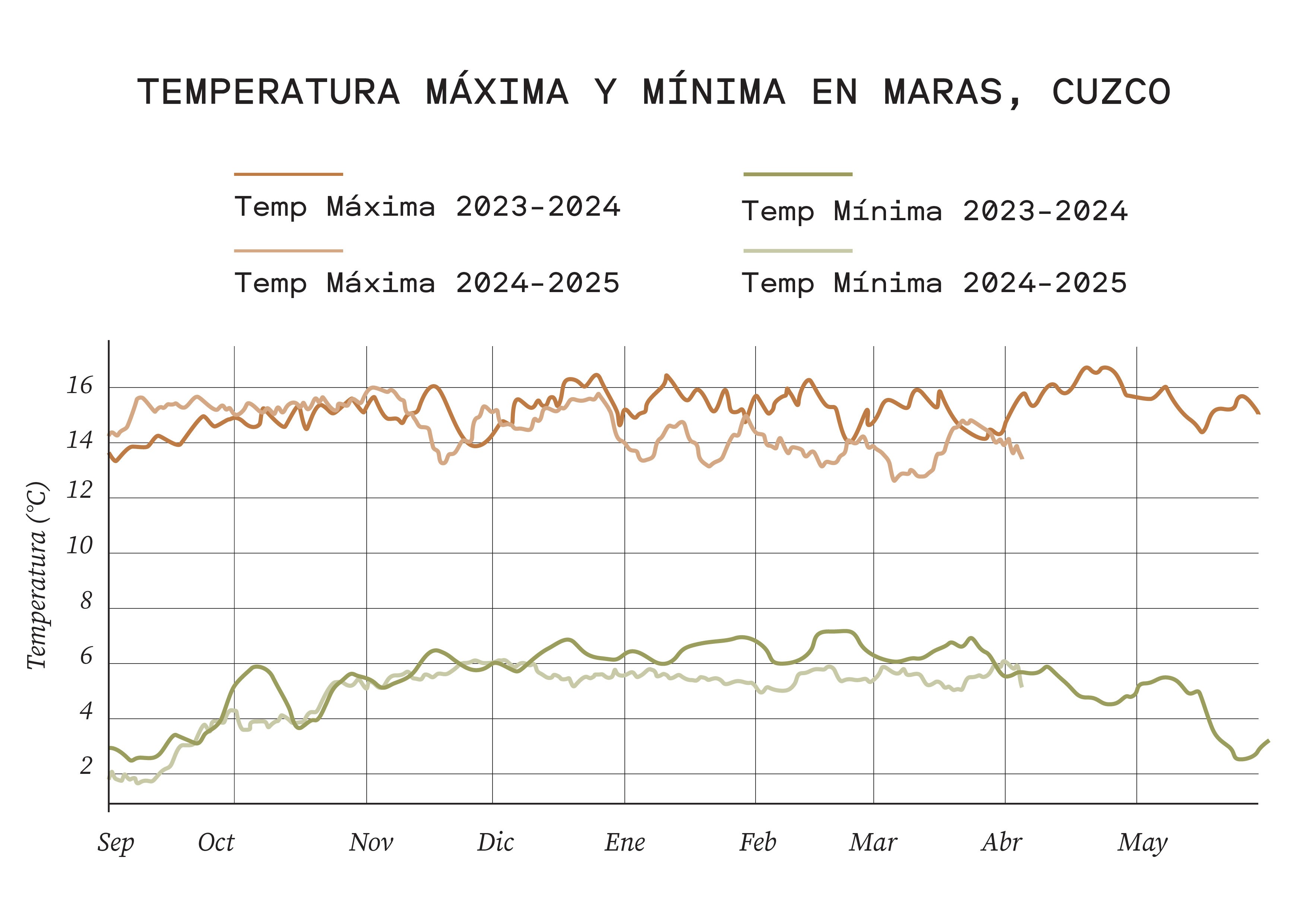

2024–2025: Intense rainfall and the advance of late blight

The 2024–2025 season presented one of the most complex scenarios of recent years. A brief La Niña episode (a phenomenon that usually cools the Pacific Ocean and alters rainfall patterns in the Andes) disrupted the usual rainfall regime in Moray, generating much higher-than-expected precipitation and colder early mornings. This combination: saturated soils, cold nights, and constant humidity favored the explosive development of late blight, locally known as rancha, caused by the oomycete Phytophthora infestans. This pathogen thrives between 10 and 20 °C, with relative humidity above 90%, conditions widely documented in the literature (CABI, 2021; Minogue & Fry, 1981).

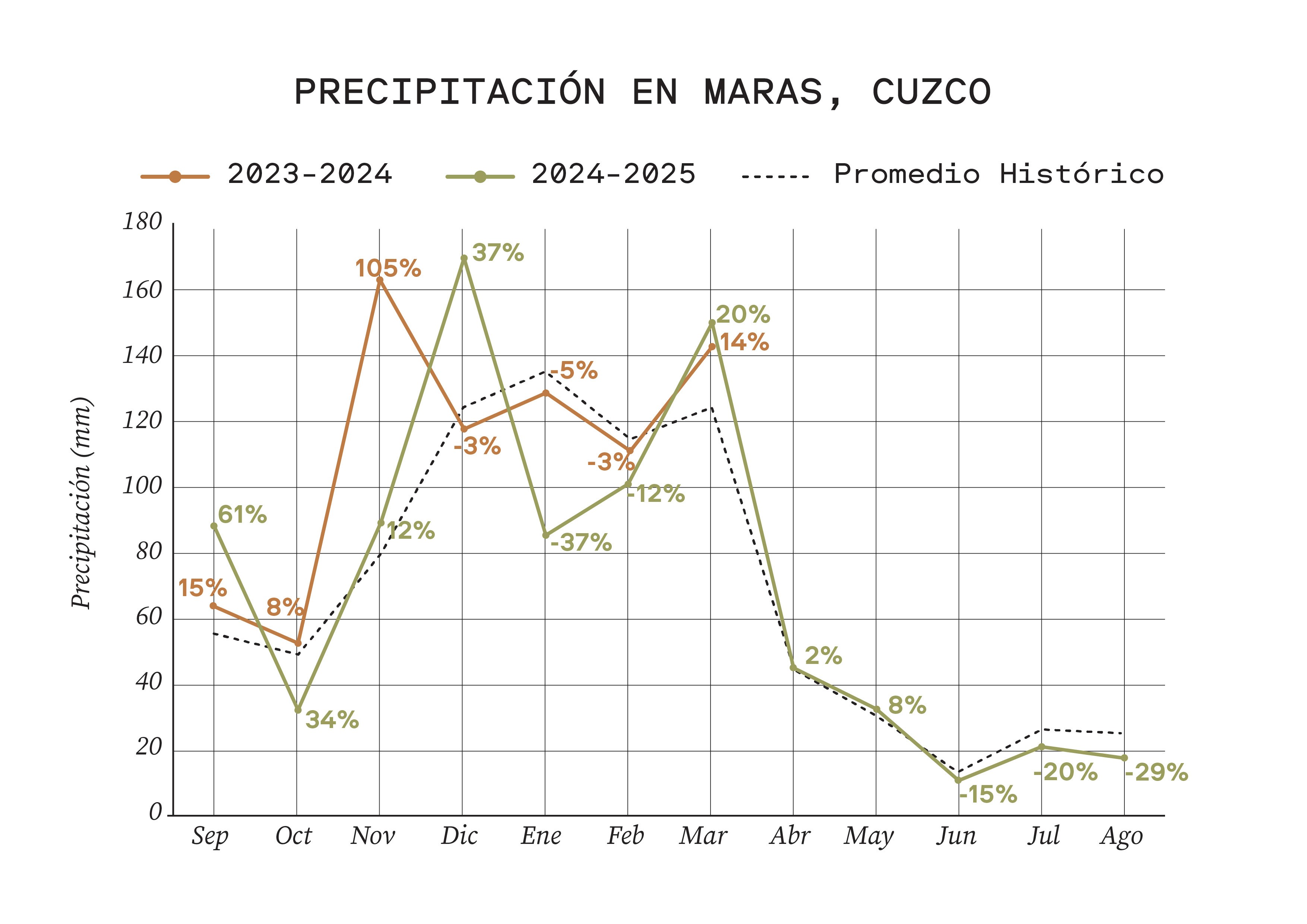

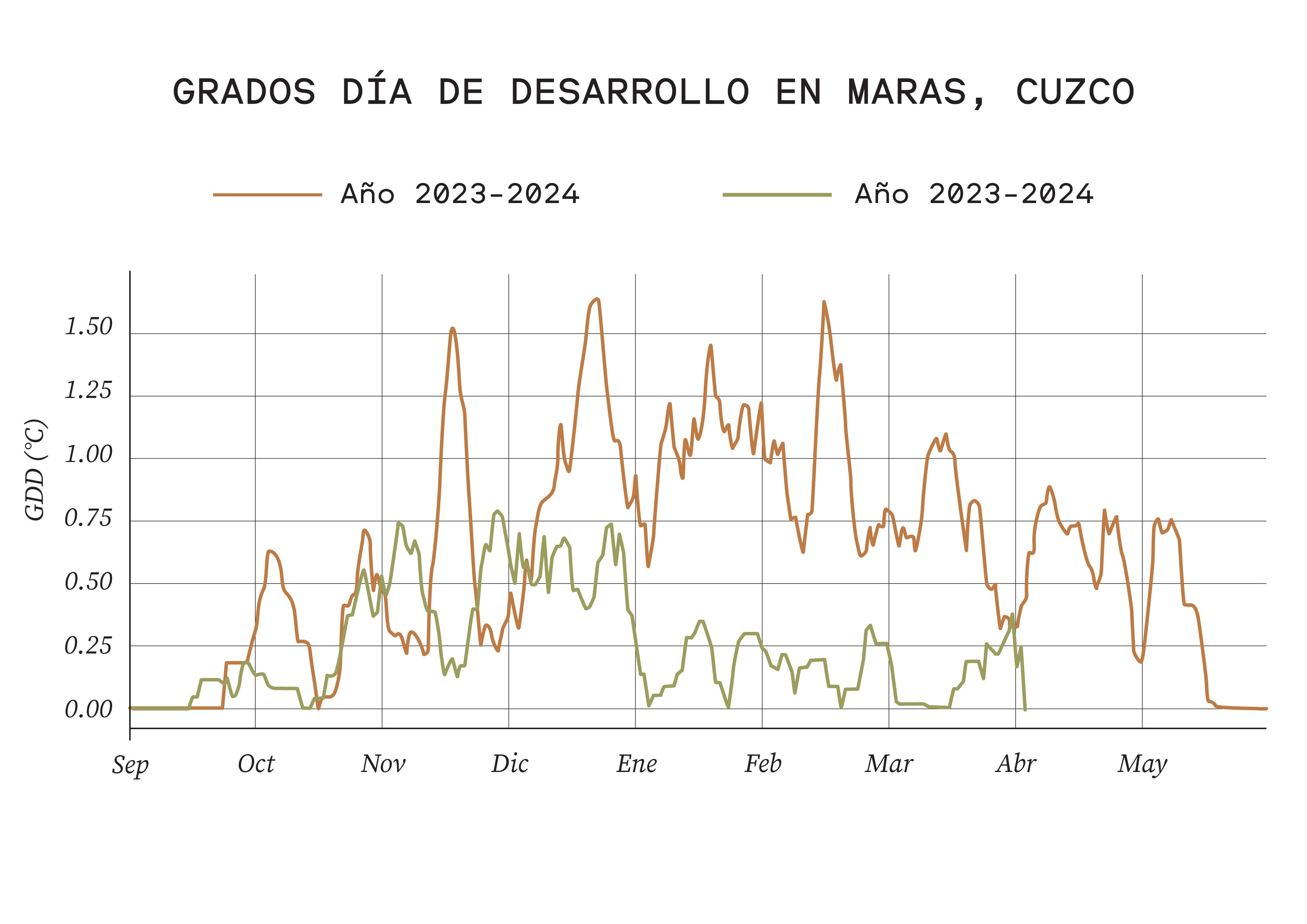

Between September 2024 and March 2025, unusually high rainfall was recorded: September and October accumulated 68 mm (12% above the historical average), November reached 160 mm (doubling previous records), and March recorded 140 mm along with temperatures below 10 °C, low accumulated heat (GDD), and relative humidity between 87 and 90%. This scenario reduced the effectiveness of fungicides, which were frequently washed off by rain, and facilitated the rapid spread of the pathogen (Annexes: Figures 1–4).

As a result, potato yield decreased by 23%, from 4,743 kg in 2023–2024 to 3,672 kg in 2024–2025 (Table 1). Traditional practices such as selecting resistant tubers or using ash had limited effectiveness under such persistently humid conditions. It is important to remember that P. infestans is not a fungus but an oomycete; this taxonomic difference directly influences its biology and the most appropriate control strategies (Gastelo et al., 2025; Pérez et al., 2001).

Photo description: Late blight attack on potatoes. Infected leaves with necrotic symptoms are visible. Late blight infection also facilitates the attack of other parasites.

Photo description: Late blight symptoms on leaves. Rounded brown lesions indicate pathogen growth. A white halo around the lesions confirms spore production, indicating that the parasite is in its reproductive and infectious stage.

The situation observed in Moray reflects a regional trend: in 2024, more than 2,000 farmers in Junín were affected by late blight, with losses of several thousand soles (AGROPERÚ, 2024). In contrast, other pests such as the Andean potato weevil (Premnotrypes spp.) continue to respond positively to ancestral cultural practices, including the use of mashua and tarwi as repellent or companion crops (CABI, 2015).

Complementary note, academic validation of a traditional solution:

A relevant case is intercropping with mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum), a traditional practice used to reduce damage from the Andean potato weevil (Premnotrypes spp.). This ancestral management has attracted scientific interest, and the International Potato Center (CIP) is currently evaluating, through experimental trials, the effectiveness of mashua intercropping as part of integrated pest management, with the aim of scientifically validating its contribution to more resilient agricultural systems (CABI, 2015; CGIAR, 2025).

Table 1. Potato production (kg) per season - Moray Farm

Season | Production (kg) | Variation (%) |

2023–2024 | 4 743 | - |

2024–2025 | 3 672 | - 23 % |

2023–2024: sequía, mínima presión de tizón y resiliencia de variedades nativas

The 2023–2024 season presented the opposite scenario. Rainfall was below normal, with October, January, and February showing deficits of 34%, 37%, and 12%, respectively, creating an environment too dry for late blight development (Annexes: Figures 1–4). In the absence of the disease, and despite water stress that reduced tuber size by approximately 20%, native varieties showed greater tolerance and maintained superior vigor. This phytosanitary stability contributed to higher production in 2023–2024 compared to the following year, demonstrating how the absence of a key pathogen can compensate for moderate drought.

2. Faba Bean (Vicia faba)

2024–2025: Intense rainfall and natural control of leafminer flies

Faba bean responded in the opposite way to potato. Intense rainfall and low temperatures significantly reduced populations of its main pest, the leafminer fly (Liriomyza huidobrensis). Soil saturation decreased pupal survival, while high humidity favored natural enemies, including predators and entomopathogenic fungi (fungi that parasitize insects and regulate their populations). This combination reduced pest pressure by approximately 70%, allowing more vigorous growth and better pod and seed development.

In production terms, the 2024–2025 season showed a 53% increase, rising from 227 kg in 2023–2024 to 347 kg in 2024–2025 (Table 2).

Table 2. Faba bean production (kg) per season — Moray Farm

Season | Production (kg) | Variation (%) |

2023–2024 | 227 | - |

2024–2025 | 347 | + 53 % |

2023–2024: Water deficit and leafminer outbreak

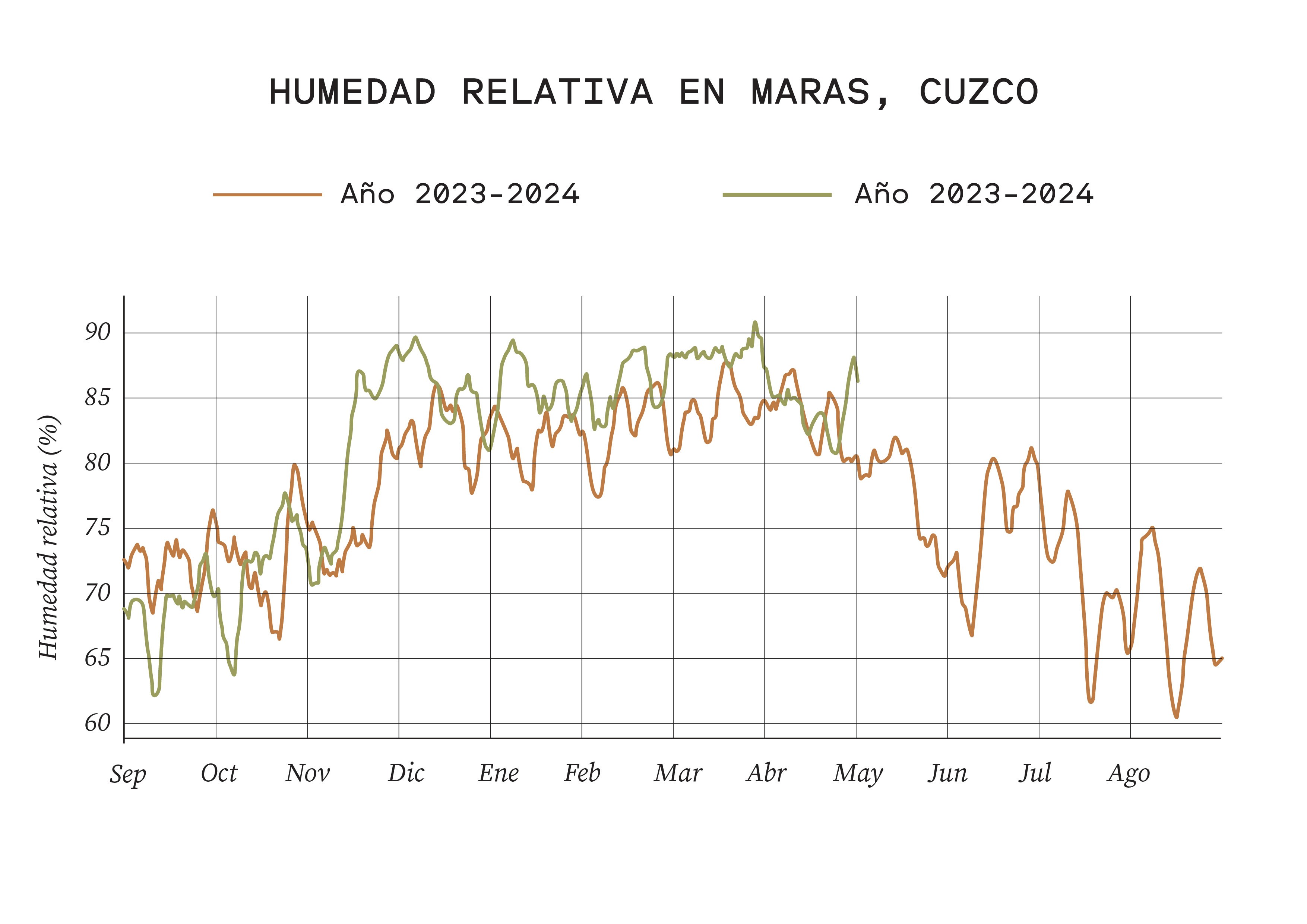

The 2023–2024 season was more challenging for faba bean. Rainfall deficits and high temperatures caused severe water stress, accelerated flowering, and reduced the number of pods per plant from an average of eight to only four or five. This phenological change (alterations in plant developmental stages) resulted in a yield reduction of nearly 40%. At the same time, warm conditions and relative humidity between 75 and 85% favored population growth of the leafminer fly. Its highly flexible life cycle can accelerate considerably: on the Peruvian coast, it has been documented to shorten from 40 days in winter to 19 days in summer (Travaglini, 1990), explaining the rapid population increases observed in dry years (Annexes: Figures 1–4).

Photo description: Larva of the faba bean leafminer (Liriomyza huidobrensis). Foliar damage caused by its feeding is visible on the leaves.

Photo description: Adult leafminer fly (Liriomyza huidobrensis). Adult size does not exceed 2.5 mm.

Implications for Andean Agriculture and Lessons for Chacra MIL

The comparison between the 2023–2024 and 2024–2025 seasons confirms that the same climatic event can generate completely opposite responses in different crops, forcing agricultural management to be rethought as a dynamic and crop-specific system. While intense rainfall in potato triggered late blight and reduced yields, those same conditions suppressed leafminer flies in faba bean and led to a significant increase in production. For Chacra MIL, this contrast reaffirms that there is no single valid strategy, but rather a set of flexible decisions that must be adjusted year by year.

This analysis highlights several key lessons. First, it confirms the importance of continuous agrometeorological monitoring to anticipate risk scenarios and adjust planting calendars, phytosanitary management, and water use. Second, it demonstrates the value of native seeds, polycultures, and traditional cultural practices—such as the use of mashua and tarwi—which contribute to natural pest control and strengthen functional biodiversity. Third, it underscores the need to optimize water management, both in years of excess and deficit, through water harvesting techniques, living mulches, and soil management.

Perhaps the most important lesson for Chacra MIL is the role of participatory experimentation with local farmers. Joint observation, field visits, discussions about native varieties, validation of cultural techniques, and shared interpretation of results enable real co-learning, where scientific knowledge and ancestral wisdom enrich one another. This collaborative dynamic not only improves management decisions but also creates space to test new strategies in a contextualized way.

From these exchanges arise questions that guide future research: How can traditional practices be better adapted to the changing rhythm of climate? Which crop combinations offer greater resilience to pests and water stress? What new techniques can be incorporated without losing cultural coherence or ecological sustainability? Answering these questions requires continued field trials, variety testing, experimental rotations, and polyculture arrangements, always with active community participation.

The experience accumulated in Moray demonstrates that integrating scientific research, traditional agriculture, community work, and gastronomic approaches can transform climatic challenges into opportunities for innovation. From its role as a space for experimentation and learning, Chacra MIL has the potential to consolidate this articulation and move toward more resilient and culturally rooted Andean agricultural systems, capable of responding creatively and adaptively to future challenges.

References:

AGROPERÚ. (2024, marzo 6). Junín: Más de 2000 agricultores pierden aproximadamente 500 hectáreas de papa por rancha. AGROPERÚ Informa. https://www.agroperu.pe/junin-mas-de-2000-agricultores-pierden-aproximadamente-500-hectareas-de-papa-por-rancha/

CABI. (2015). Gorgojo de los Andes. PlantwisePlus Knowledge Bank, Pest Management Decision Guides, 20157800286. https://doi.org/10.1079/pwkb.20157800286

CABI. (2021). Phytophthora infestans (Phytophthora blight). CABI Compendium, CABI Compendium, 40970. https://doi.org/10.1079/cabicompendium.40970

Gastelo, M., Bastos, C., Ortiz, R., & Blas, R. (2025). Environmental impact and phenotypic stability in potato clones resistant to late blight Phytophthora infestans (Mont) de Bary, resilient to climate change in Peru. PLOS ONE, 20(2), e0318255. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0318255

Minogue, K. P., & Fry, W. E. (1981). Effect of temperature, relative humidity, and rehydration rate on germination of dried sporangia of Phytophthora infestans. Phytopathology, 71(11), 1181-1184. https://www.apsnet.org/publications/phytopathology/backissues/Documents/1981Articles/Phyto71n11_1181.pdf

Perez, W. G., Gamboa, J. S., Falcon, Y. V., Coca, M., Raymundo, R. M., & Nelson, R. J. (2001). Genetic Structure of Peruvian Populations of Phytophthora infestans. Phytopathology®, 91(10), 956-965. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.10.956

CGIAR (2025). CGIAR en Instagram: Iván Manrique is the Curator for Andean Roots and Tubers at the International Potato Center genebank. (2025, January 27). Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/DFVK1keiH8R/

Mujica, N. (2015). Modelo fenológico dependiente de la temperatura de la mosca minadora Liriomyza huidobrensis (Blanchard) (Diptera: Agromyzidae). 57. Convención Nacional de Entomología, Huánuco, Perú, 2–5 de noviembre de 2015. Lima, Perú: Sociedad Entomológica del Perú.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2025, January 9). January 2025 update: La Niña is here. NOAA. Recuperado de https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/january-2025-update-la-nina-here

Annexes:

Fig. 1. Comparison of historical precipitation and precipitation during the 2023–24 and 2024–25 growing seasons.

Fig. 2. Growing Degree Days (GDD): Daily accumulated heat above 10 °C.

Fig. 3. Maximum and minimum temperatures corresponding to the 2023–24 and 2024–25 growing seasons.

Fig. 4. Relative humidity in Maras–Cusco during the 2023–24 and 2024–25 growing seasons.

During the 2024–25 season, higher relative humidity values were observed compared to the previous 2023–24 season. These values ranged from 82–85% up to 90% from mid-November through February. In March, humidity intensified further, remaining above 87% throughout the entire month. Together with lower temperature values and reduced Growing Degree Days (GDD), these conditions created an ideal environment for the proliferation of late blight during the 2024–25 season.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Final Agroclimatic Report – Chacra MIL

1. Where is Chacra MIL located?

Chacra MIL is located in Moray, Cusco, at 3,550 meters above sea level. It functions as an experimental observation farm, where the influence of high-altitude climate on Andean crops, their health, and their yields throughout the year is studied.

2. Which crops were analyzed?

Two crops that are fundamental to Andean food systems and cuisine were analyzed:

Potato (Solanum tuberosum), the historical basis of the high-Andean diet.

Faba bean (Vicia faba), a key legume due to its nutritional value and culinary versatility.

3. Why does climate generate opposite effects in potato and faba bean?

Because each crop responds differently to humidity and temperature.

In potato, intense rainfall and high humidity favor diseases.

In faba bean, those same rainy conditions reduce pests that thrive under dry and warm conditions.

This contrast shows how a single climatic event can have cross-cutting impacts depending on the crop.

4. What is late blight (“rancha”) in potato, and what causes it?

Late blight, locally known as rancha, is a disease that affects potato leaves and tubers.

It is caused by Phytophthora infestans, a microorganism that develops under high humidity, persistent rainfall, and cool temperatures. When it occurs, the plant weakens rapidly and production can be significantly reduced.

5. What is the faba bean leafminer and what causes it?

The leafminer is a pest caused by a small insect called Liriomyza huidobrensis. Its larvae live inside faba bean leaves, forming tunnels that disrupt photosynthesis. This pest increases mainly during dry and warm years, weakening the plant and reducing productivity.

6. What is the disease triangle?

It is a simple way to understand why diseases and pests occur.

Any outbreak results from the coincidence of three elements:

The causal agent (pest or pathogen)

The host (the plant)

The environment (temperature, humidity, and rainfall)

If one of these factors changes, the problem can decrease or intensify.

7. Can anything be done if climate cannot be controlled?

Yes. Although climate cannot be modified, agricultural practices can be adapted.

Some strategies include:

Adjusting planting dates

Using more resistant native varieties

Associating different crops

Improving soil and water management

These measures help reduce risks and protect crops in difficult years.

8. What role do biodiversity, soil, and associated crops play?

A diverse and living farming system helps keep plants healthier.

The combination of crops such as potato, faba bean, maize, mashua, and tarwi:

Naturally reduces some pests

Improves system balance

Strengthens resilience to climate variability

Biodiversity functions as an invisible ally of the farmer.

9. What role does the community play in this work?

The community is a central part of the process.

Participatory experimentation, field visits, and the joint interpretation of results enable co-learning, where scientific knowledge and traditional knowledge complement each other to support better management decisions.

10. What productive results were observed?

The clearest case was faba bean, whose production increased by 53% during the 2024–2025 season, rising from 227 kg to 347 kg. This increase was associated with higher rainfall, lower pest pressure, and better conditions for crop development.