From Past to Present

Máximo Champi Palomino´s Ceramics as a Cultural Bridge

24/01/24

Macarena Tabja

10 min

The hands of Cusquenian ceramist Máximo Champi Palomino mold the brown clay in front of him. He is in his workshop, in the Santa Ana neighborhood in the city of Cusco, where the first human settlements were established during pre-Inca times. Archaeological excavations in the area have found evidence of a ceramic enclosure; the tools, the oven, the clay and the pieces created. Pieces now fragmented by the passage of time and to which Máximo returns, seeking to learn about the ancestral techniques with which they were made. In his fingers he carries the marks of his ancestors and in his mind the purpose of keeping alive the artistic processes of the millenary cultures that influence his work, such as Chanapata and Marcavalle ceramics. Among the traces that these pre-Columbian settlers have left as a sign of their presence, there are flat base vessels, dyed in black and with incised decorations. These are pieces that do not follow a rigid pattern, the manual work is revealed in the imperfections and in their differentiated strokes. That unrepeatability is what inspires Máximo as much as a fragment of Chanapata pottery he has at home, where the traditional iconography has been disarranged. He interprets this act as an artist's quest to create new concepts, connects with that intention and firmly embraces his passion as a ceramist.

Máximo Champi works the clay by hand.

The ceramist in his workshop in the neighborhood of Santa Ana, Cusco.

The fact that Máximo's workshop is located near these ancient communities is not the only coincidence that links him to ceramics. In a conversation with his mother, he discovered that the art is rooted in his Andean heritage. Originally from the village of Yanaoca in Espinar, his predecessors were engaged in the usual chores of farming and herding sheep. But just as the Chanapata artist broke out of the mold, so did Máximo's great-grandmother. Her name was Santusa and she was a ceramist. At 4,000 meters above sea level, Santusa used the materials she found in the area and created pieces for everyday use, such as plates and small recipients. This unexpected link with his great-grandmother surprises Máximo and compels him to introspection. He remembers himself as a child, playing with clay, fascinated by that plasticity that allows him to do and undo and then re-create a different piece. These memories are then combined with his talent and the curiosity that leads him to investigate and study the techniques of the cultures that preceded him.

The pieces he creates are born from the earth and are also formed from it. Explorations during the dry season to different Cusco quarries in Saccsayhuaman, San Sebastian, San Jeronimo and Chinchero to find the right clay are the beginning of his artistic process. Visits to museums to study the components of pre-Inca ceramics to repeat these formulas speak of his effort to revalue ancestral knowledge and local resources. Trips to the towns of Raqchi and Urco to collect slate and volcanic stones complete the original recipe of a ceramic that resists high temperatures and that, with Máximo's work, also resists being forgotten.

In the quarries of San Jerónimo, where he collects the clay he uses to craft his pieces.

Volcanic rock which also forms part of the material used by Máximo for his pieces.

With his fingertips as his only tool, Máximo shapes these malleable blocks, applying the same technique used by pre-Hispanic cultures from the south to the north in the elaboration of their utensils. Each piece has its own character, its "little charm" as he describes it. Here, perfection is not necessary when there is something much richer, such as inherited wisdom and the evolution it undergoes when shared. New pieces, new designs, new tools result from this transmission of knowledge. Máximo's pieces are evidence of this. He is inspired by pre-Inca iconography and the highland landscapes in which he lives immersed. His predecessors drew hills on their pieces. In his, Máximo fuses them with other elements of nature, such as farms, rivers and lagoons. While the ancestors incised their ceramics with the city of Cusco in the center, he adds lateral lines to represent the union of the territories. Like the Chanapata artist, Máximo reinterprets symbologies without subtracting from the original significance.

Máximo adds his own inspiration to ancestral iconographies.

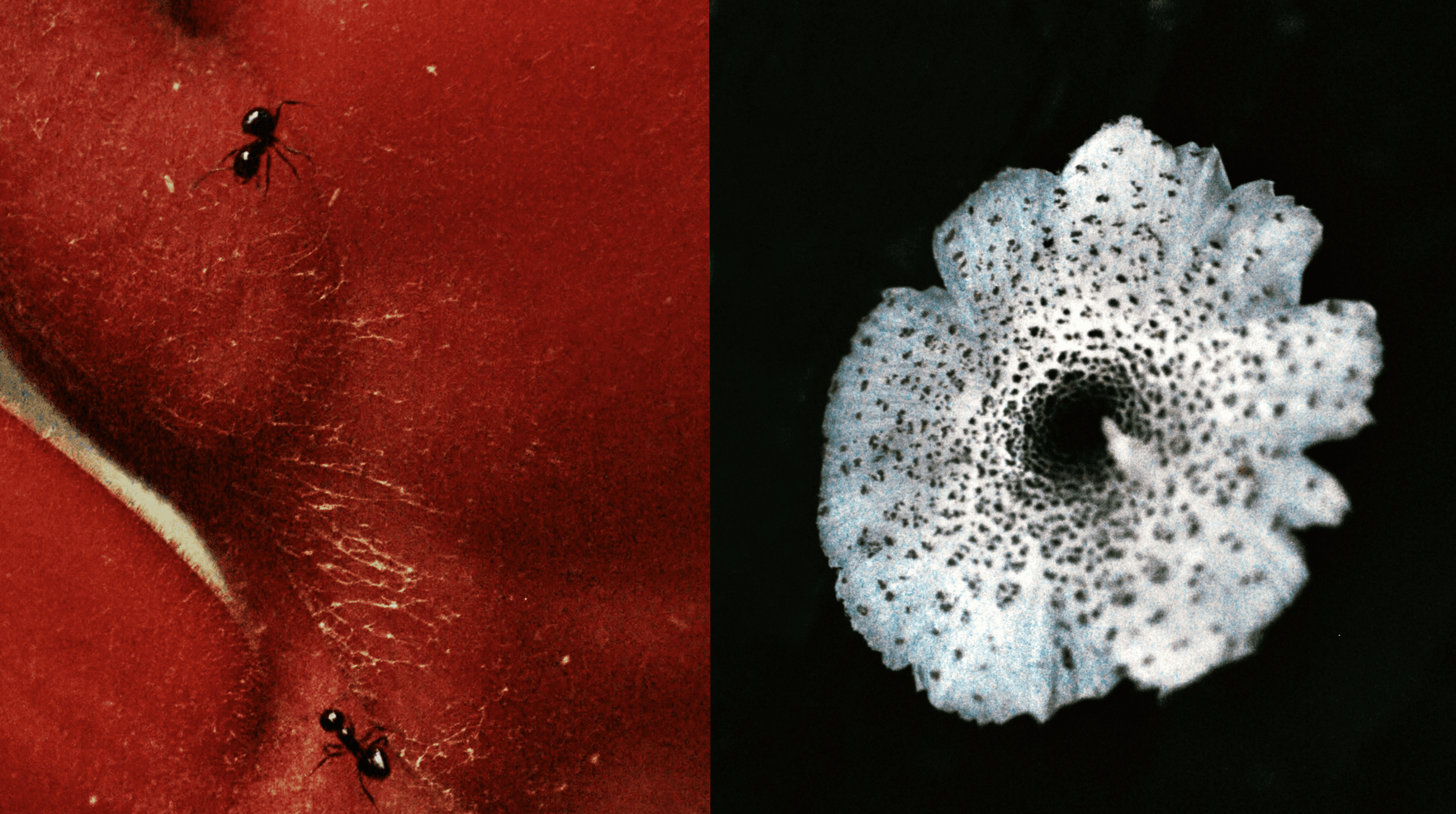

The inverted draft oven that he uses for firing his pieces is also proof of the evolution of transmitted knowledge. He asserts that the knowledge obtained from all the ovens over time has been put into this one. It is ancestral, of Japanese techniques but built by hand in his workshop. Layers of brick, clay, straw and sawdust support this structure that uses wood as energy and cooks unevenly. The fire distributes its heat in different measures inside the oven and this variation of temperatures derives in pieces that are different within their homogeneity and are impregnated with knowledge and traditions. With dried eucalyptus leaves he smokes the hot pieces, painting them black and with beeswax he fixes the ceramic, turning it impermeable.

The inverted draft oven where he bakes his pieces.

Layers of brick, clay, straw and sawdust support the oven structure.

Maximo closes the oven with bricks and paper before lighting it so that the ceramics can start cooking.

The mountain of the Seven Colors -or Vinicunca mountain- is also present in Máximo's work. In addition to the black tone he obtains from the eucalyptus leaves, his pieces are often dyed in the colors that have been traditionally used in the Cusco area. The natural pigments that result from passing the pebbles of this mountain through a mortar are also subject to a process of research and formulation. The reds, yellows, browns, creams and violets are the ones that have withstood the highest temperatures in their oven, "they have passed the test of fire," says Máximo. The origin of these colors is millions of years of geological processes, turning them into a sort of living witnesses of ancient cultures. Permeated in Máximo's pieces, a chromatic circle of techniques and resources is composed with a memory of the past and a vision of continuity.

Eucalyptus leaves are steamed around the hot clay to dye them black.

The ceramic utensils created by past cultures speak of the fundamental link that has existed for thousands of years between traditional beverages and the development of Andean communities. This is the case of the raquis, these vases used to ferment and store the chicha offered to the Pachamama during the work on the farm and the celebrations of the worlds from above and below. Máximo reflects on the parallel he finds between chicha and ceramics, both go through a long process where physical changes occur in the ingredients to become something more. The spiritual charge that is also involved in that transformation ends up linking everything they represent: the rituals, the sorrows, the joys, the prosperity of the land. In his workshop, Máximo is going through his own process to create raquis to store not only the chicha, but also the ancestral knowledge and the Andean connections with the moon, the sun and the stars. The raquis will be used by the communities of K'acllaraccay and Mullak'as Misminay, who cultivate MIL's chacra and still maintain their inherited knowledge and traditions. Máximo also works on tocapus, the phonetic symbols that pre-Inca cultures used to draw on their textiles and ceramics to narrate their daily life, their territories and their beliefs. Máximo interprets these symbologies of geometric and linear shapes, he knows how to read them without having to speak the same language.

The raquis are traditional vessels where chicha is fermented and stored for carrying it to work in the fields.

Tocapus are phonetic representations that pre-Inca cultures drew on their textiles and ceramics to narrate their daily life, their territories and their beliefs.

Musical ceramics opened a world to Máximo that he describes as happiness. Giving sound to his pieces is to vivify the clay, the stones and the mountains. They are pieces that whistle history to be heard in the present. The evidence of the ways of life of the past, then, is no longer only visual; ancestral sounds join the work to revalue and transmit that human and cultural legacy. As he says, "you have to be well connected to create something incredible". In light of his pieces, Máximo, the ceramist by passion and heritage, is.

Photos: Gustavo Vivanco León