Perspectives of Masato

A powerful transmitter of Amazonian knowledge.

28/11/24

Ariadna Oliveri

11 min

In the Upper Amazon, between the winding Huallaga and Marañon rivers near the basins of its tributaries, are the native Shawi people. Entering these forests, and the Peruvian Amazon, is not only a physical act, it is deepening and immersing oneself into the cosmovision of these lands. And, although it may seem complex, it is rather an organic action of the environment. Nature is a significant and essential part of their being and existence, which leads them to explain and interpret the world around them in different ways, to support their culture and heritage. It is their responsibility to observe, know and interpret it. In these interconnections, animism is the backbone of the Amazonian cosmovision, a belief based on the idea that any human or non-human agent is a holder of the soul or spirit, life and consciousness (Olórtegui Sáenz, 2016).

“Nature is life and life speaks, but many have forgotten how to listen to it. If we don’t hear each other amongst humans, even less will we hear the messages of trees, birds, animals or water”. (Conclusions of the Indigenous Peoples' Encounter, 2008).

They listen, but not only do they listen, they also attend and understand her. They respect her times, her stations and her care.

It is hot, it's August and the harvest of some crops is about to end. In the daily life of Nuevo Progreso, one of the Shawi communities to which we had the pleasure of being invited by Dr. Carol Zavaleta's team and her Biokusharu project, an important act was about to take place; to obtain what nature offers them: food and soul.

Harvests are a cause for celebration. Agriculture and water are pillars for the Shawi people, fundamental to understanding their ecosystem. And what is obtained is the gift for staying in harmony with their environment (Chanchari Lancha et al., 2012). If we talk about the land, the protagonists are the roots and tubers, present in their daily life.

Chacra de la comunidad de Nuevo Progreso

Manos cosechando en la comunidad de Nuevo Progreso

Cosecha de sachapapas en la comunidad de Nuevo Progreso

Undoubtedly, the indispensable yucca (Manihot esculenta) is their staple food and that of most of Latin America, Asia and Africa, being the fifth most productive crop worldwide for human consumption (Otálora et al., 2024). Domesticated for over 10,000 years in the southern margin of the Amazon basin, yucca is considered a staple food since it constitutes the daily diet of the Shawi people. As a rich source of carbohydrates, it provides an important part of energy in their diet (Wooding & Payahua, 2022). But to be honest, it is more than a staple food. Its value transcends the purely nutritional: it is a central element of community life that takes on meaning in different layers of depth. A bond that is strengthened every time it is sown, harvested or prepared.

And if there is something that the countries and communities that share this food have in common, it is its use and preparation techniques. Mostly, due to the toxicological characteristics of this root, the step prior to any future processing is boiling. Yucca contains linamarin, a chemical compound that has the capacity to release cyanide and be toxic. For these reasons, it is recommended to boil it to remove high concentrations of this toxin and ensure its safe consumption (Castro-Moreira et al., 2021). If wanted, it could also be fried, roasted, made into flour or traditional alcoholic beverages such as masato.

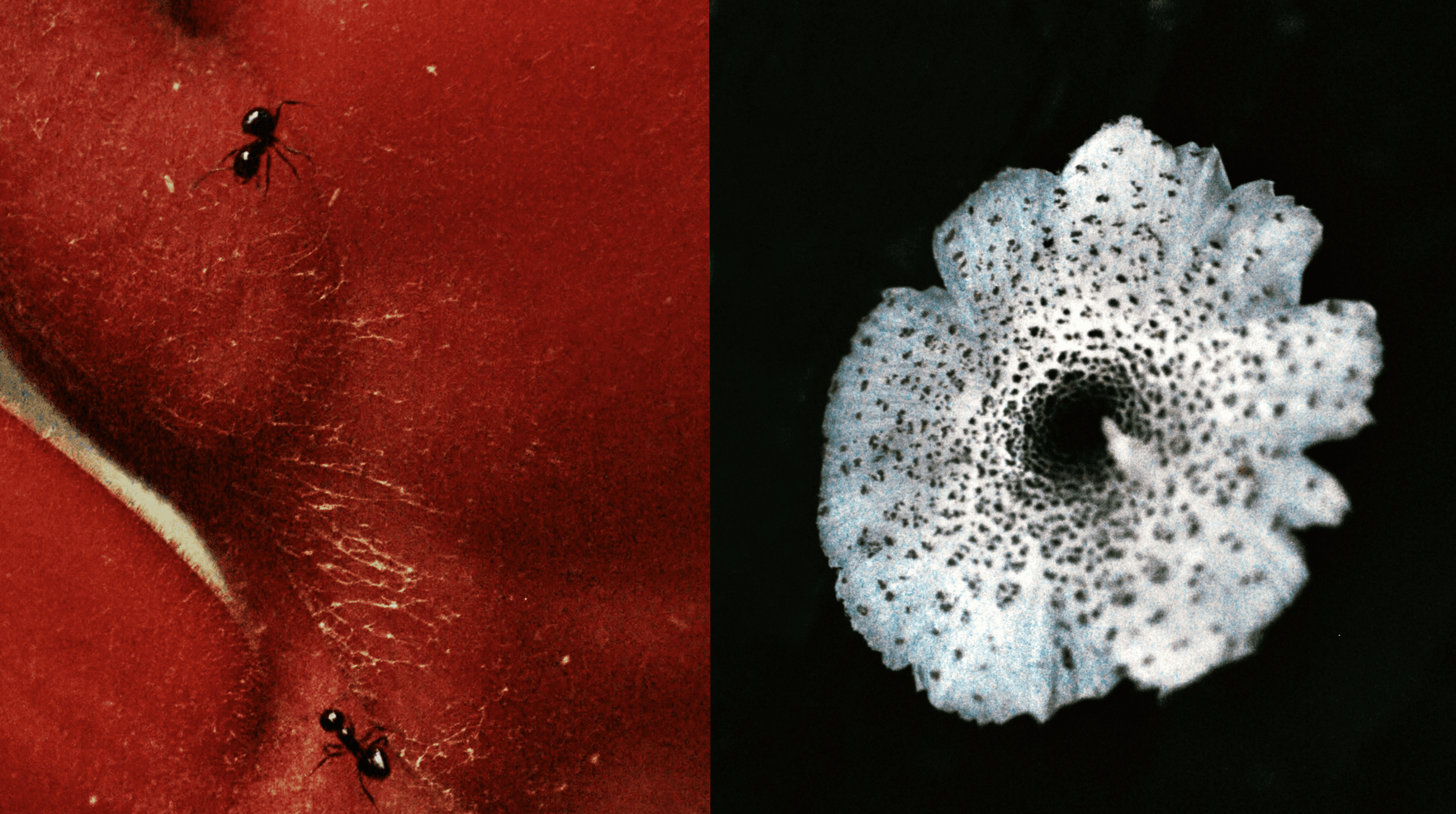

It is early in the morning. We arrive at the home of Isidro Chanchari, the community's vegetalist and wiseman, to introduce ourselves and explain the reason for being there. His son-in-law and daughter Yeny are also present. I notice their hands are dyed the same color as their faces. Huito, they said. A fruit from which, if grated, a bluish black pigment is obtained, used as a natural dye for aesthetic and identity purposes, but also ceremonial or protective.

We are welcomed and seated in their common area. Fernanda Huiñapi, woman, mother and wife appears shortly after; without warning she serves us, in a beautiful ceramic called mocahua, abundant masato. To receive this substance is not only an act of drinking, it is to receive both physical and cultural sustenance. It is an act of welcoming, recognition and hospitality that invites you to inclusion in the community.

Before handing us the mocahua, I observe the previous path of the masato. She strains the mixture and serves it, but not before removing the leftover fibers left by the yucca. She gently wipes the edge with her thumb and index finger and extends the mocahuas to us. There is a reason behind every gesture and detail. So I wonder if there is also an established order in serving masato and a social structure around this drink. And what about that skirt Fernanda is wearing? Does it have something to do with the reddish color she wears? I imagine there will be plenty of time to answer all these questions that float around in my head.

Once in my hands, I observe it. In front of me, a peculiar and intense purple color. Until then, I had thought that this drink could have a range of colors that varied from white to yellow depending on the ingredients used. For that same reason, I learned that the abundance of products according to their harvesting made incursions into other variants of masato, as it happened at this time with the masato of purple sachapapa. And yucca, of course. Junior, the son of Isidro and Fernanda, collaborator of the Biokusharu project and also the communication link between the women and us, tells us that in his community, on special occasions, masato is made with sprouted corn, pijuayo and even with sugarcane leaves and fruit, typical of the festivities of San Juan Bautista.

Sachapapa morada utilizada en elaboración de masato

Proceso de rallado de camote rosado para añadir en la elaboración del masato

Initially acidic, creamy and unctuous in texture. Slightly sweet and full-bodied. Alcoholic and effervescent, but not pungent. Characteristic fermentation; apparently mild. With earthy and sourdough notes. A first sip has me convinced. It's enough to keep on delving into such a range of colors, preparations and women and mothers behind each fermentation.

To speak of masato is to speak of how this beverage is transformed from yucca, mainly, to alcohol. And how human resourcefulness sharpens when resources do not guarantee food safety. Drinking water is not always a commodity that everyone can enjoy. Under these circumstances, a form of consumption that could be substituted for water as a safe and nutritious source of hydration may have emerged (Jimenez et al., 2022). Masato nourishes body and soul. Perhaps because it is also both. And in this collaboration that nature provides between the initial food, fermentation, the bacteria and yeasts that follow, the water, the mocahuas and the elaborating hands tend bridges between the mundane and the spiritual of the environment, being masato and alcohol the mediators and messengers between both dimensions. A bridge commonly extended throughout history that ties together the ingestion of alcohol and the connection with deities (Santos Granero, 2018).

Once in the communal area, we met the women and mothers who were going to participate in this encounter. Mater introduces itself to them and to the authorities of the community to start the day. A few hours of heat and intense work are ahead of us. Before heading to the chacra, we share conversations around masato. Observing firsthand how the consumption of this beverage takes place in the community, I ask everything that makes me curious.

The questions ask themselves as Fernanda, Santusa, Sabina and Norith serve us one after the other without the possibility of refusal. Suddenly, I find myself with five mocahuas overflowing with masato, one more different than the previous one. To Fernanda's purple sachapapa masato, four other surprises were added to my palate. I ask about the number of days they leave it to ferment and whether they masticate it or not. There is a notorious alcoholic difference in those that are masticated: they are strong and with character; the kind that make you close one eye because of their presence. Fermentation varies between 24 and 72 hours, with 24 and 48 hours being the most common in my registration of both communities.

Cuatro variedades distintas de masato según su elaboradora de la comunidad de Nuevo Progreso

Masato de la comunidad de 10 de Agosto

The chemistry of masato reflects its balance between nature and wisdom. Yucca, but also grated sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) or purple sachapapa (Dioscorea trifida L.) are essential raw materials for the transformation into this beverage. These starchy roots are made up of long chains of sugars that resist fermentation (Ellix Katz, 2003). To release these fermentable sugars and for the magic (of fermentation) to happen, the starch chains must first be broken down by amylase enzymes present in the saliva of these wise women. Each woman and guardian of her recipe has her own technique, her own fermentation period or the use of certain ingredients or other resources. Thus, with the passage of time, the use of saliva is not an essential rule for the elaboration of masato. Other techniques and foods can also undertake the production of amylases. This opens up a world of possibilities around the concept of masato.

In more detail, to be masateado (a term that refers to being inebriated with masato), a fermentation process must take place, which is vital to obtain alcoholic volume in its final result. For this, everything starts in the chacra. After planting and harvesting, the role of Shawi women and mothers is to peel the yuccas in the same chacra and wash them in the creek before reaching their homes. With the firewood lit, they place the white or yellow yuccas in the pot for cooking. At the same time, they grate white, yellow, pink or purple sweet potatoes according to the taste and personality of each elaborator. On special occasions they add sprouted corn or boiled purple sachapapa.

Yucas peladas listas para hervir y utilizar en elaboración de masato

Masato especial de sachapapa morada

When the yucca is soft, still steaming, it is time to crush it into a cream-colored paste. It can be masticated, facilitating the fermentation and the available sugars, or not. Sugar is another variable to be decided by the person who makes it. They mix this paste with abundant water and the previously grated ingredients. Finally, with all the ingredients incorporated, fermentation takes place.

Rogelia Pizango removiendo la olla con las yucas hervidas para hacer la pasta

Adición de camote rallado y agua a la pasta de yuca hervida para su fermentación

The watery medium and the sugars provide an ideal environment for the growth of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria responsible for alcoholic and lactic fermentation, respectively. While the yeasts turn the sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide, giving the paste its alcoholic character, the bacteria transform the sugars into lactic acid, which causes a decrease in pH, favoring an acidic environment which contributes to its preservation and protection from unwanted contamination. In the first stages of fermentation, lactic acid bacteria predominate, increasing acidity. As the pH decreases, the environment becomes more selective. This leads to yeast becoming more important, increasing alcohol production over time. Usually, masato contains between 2 and 6 %ABV, a variable that varies according to the alcoholic and acidic taste of each woman and family (Rebaza-Cardenas et al., 2021).

Rogelia Pizango colando el masato ya fermentado para servir en mocahuas

"If people say they don't care about fermentation, it's because they haven't thought about it. Because it impacts everyone's life. Doughs, cheese, chocolate, wine. When you think about the biology of what happens in a pot or a jar or a fermenter. Anything. If you want to keep it going you have to share it with somebody. You have to give it to somebody. You have to offer it." (David Zilber, 2024)

As we exchange mocahuas, conversations and lessons flow. As a spectator I observe the interactions between the men and women of the community and their relationship to the drink. Each woman serves her husband first, if they are in the same space. They are then followed by family members in order of age. It is also common to offer masato to visitors first. Masato is always shared. As Daggett (1983) says, “taking masato with someone is a significant sign of friendship among the Chayahuita; anything else, such as a greeting and a conversation, is very superficial if masato is not taken.”

Isidro Chanchari, vegetalista y sabio de la comunidad de Nuevo Progreso bebiendo masato

The exchange is quick. Sometimes they drink in one gulp and return the mocahua to drink again. The occasion dresses the rest of the women in a red skirt, like Fernanda's. The pampanilla, as they call it, is the characteristic skirt worn to serve masato in the communities of the Shawi people.

As in Nuevo Progreso, in the Shawi community of 10 de Agosto we are welcomed with masato. The women arrive with their red pampanilla and we interact with them. After the introductions, Rogelia Pizango, who opens the doors of her house along with her husband Manuel, begins to offer us full mocahuas, before and after going to the chacra. Once we are back and waiting for the food, there is time for conversation with the women. They tell me that masato is one more member of the family. It is always there, but it is indispensable on certain occasions; in community work, in celebrations, showing hospitality or as a symbol of friendship. It strengthens interpersonal relationships. The only time you should not drink masato is if you are on a diet, that is, if you feel unwell.

I can confirm what they tell me. With Mater and the women and mothers of the 10 de Agosto community, we hold a cooking activity in which we share recipes and flavors. Previously, along with Junior, we went in search of some ingredients to complete the recipes. We stop by the house of Senaida Torres, who first offers us two mocahuas and masato. We leave her house with a coconut, sacha culantro, a citron and the promise to go to her chacra when we return. On the way back to Rogelia's house, we stop to pick up other ingredients at Carlota Mapuchi's house. First masato, then the rest.

While cooking, we water our mouths with masato. As well as the preparations. While we drink and work together, I observe the laughter that has accompanied these days. The sharing too. And the shared laughter; not without masato.

“Masato, we understand, is about nurturing connections: between friends, family, and neighbors; between those who live now and those who came before; and between the people and their place, a landscape woven with threads of myth, history, and lived experience, charged with meaning” (Wingfield & Gilmore, 2019).

I leave Loreto listening, attending and assimilating. Wanting to continue tasting identities and sharing laughter.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

Castro-Moreira, Y., Cristellot-Pinto, F., Murgueitio-Adum, N., Gómez-Salcedo, Y., & Rosero-Delgado, E. (2021). Efecto del procesamiento tradicional de la yuca (Manihot esculenta) y derivados sobre el contenido de glucósidos cianogénicos. Revista Científica INGENIAR: Ingeniería, Tecnología e Investigación, 4(8), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.46296/ig.v4i8.0033

Chanchari Lancha, M., Chanchari, A., Chanchari, M., Pizango, E., Lancha Huansi, E., & Chanchari Rafael. (2012). Mitos Shawi sobre el agua.

Daggett, C. (1983). Las funciones del masato en la cultura chayahuita. InstitutoLingüísticodeVerano, 301–310.

Ellix Katz, S. (2003). Wild Fermentation: The Flavor, Nutrition, and Craft of Live-Culture Foods.

Jimenez, M. E., O’Donovan, C. M., Ullivarri, M. F. de, & Cotter, P. D. (2022). Microorganisms present in artisanal fermented food from South America. En Frontiers in Microbiology (Vol. 13). Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.941866

Olórtegui Sáenz, J. C. (2016). LA NATURALEZA EN LA COSMOVISIÓN DE LOS PUEBLOS ORIGINARIOS DE LA AMAZONÍA PERUANA * (Issue 28).

Otálora, A., Garces Villegas, V., Chamorro, A., Palencia, M., Combatt, E. M., & Salcedo Mendoza, J. (2024). ‘Cassava, manioc or yuca’ (Manihot esculenta): An overview about its crop, economic aspects and nutritional relevance. Journal of Science with Technological Applications, 16, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.34294/j.jsta.24.16.95

Rebaza-Cardenas, T. D., Silva-Cajaleón, K., Sabater, C., Delgado, S., Montes-Villanueva, N. D., & Ruas-Madiedo, P. (2021). “Masato de Yuca” and “Chicha de Siete Semillas” Two Traditional Vegetable Fermented Beverages from Peru as Source for the Isolation of Potential Probiotic Bacteria. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-021-09836-x

Santos Granero, F. (2018). Fuegos sagrados, cosmogonías solares e integración conceptual en la Amazonía andina. 56, 129-160.

Wingfield, A., & Gilmore, M. P. (2019). Three days of Masato. ISLE Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 27(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/isle/isz084

Wooding, S. P., & Payahua, C. N. (2022). Ethnobotanical Diversity of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) in the Peruvian Amazon. Diversity, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/d14040252